Behind The Painting: The Wounded Deer

Frida Kahlo’s The Wounded Deer (1946) confronts the viewer with an image that is at once unsettling and enigmatic. A small hybrid figure, a stag bearing Kahlo’s own face, is pierced by nine arrows and set in a dense, almost suffocating forest. Every detail, from the lifted hoof to the break in the branch beneath it, seems charged with meaning yet resists a simple explanation. In this painting, private pain, cultural symbolism, and personal myth converge, creating a space where suffering becomes both intimate and public. This article examines how Kahlo channels her physical and emotional trials into visual language and how the painting’s layered references, from pre-Columbian to Christian, offer insight into her enduring artistic vision.

The Painting

In The Wounded Deer, Kahlo portrays herself as a hybrid of human and animal, combining her own head with the body of a deer and antlers extending from her skull. The deer stands with its legs in motion, the front right leg lifted as if injured. Nine arrows pierce the deer's body, each wound bleeding visibly. The scene is set in a forest, with nine tree trunks on the right and a broken branch in the foreground, likely detached from one of the nearby trees. The broken branch is emphasized through careful detail, drawing attention more than any other element on the forest floor.

Frida Kahlo, El venado herido, 1946. Oil on masonite. Private collection.

Kahlo’s face meets the viewer’s gaze with stoic composure, showing little expression of pain. Her head and neck remain upright and alert, while a set of deer ears emerges behind her own. In the background, a body of water is visible through the trees, and a bolt of lightning descends from a bright white cloud, contrasting with the otherwise calm sky. In the lower left corner, the word “carma” (karma) appears, following the artist’s signature and date.

The painting is dominated by green, brown, and gray tones, with small touches of blue and red. Its scale is modest, measuring only 22.4 by 30 centimeters.

The Artist

Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón (1907–1954) was born in Coyoacán, Mexico, to a German father and a mestiza mother of Purépecha descent. Her bicultural heritage and upbringing in post-revolutionary Mexico shaped her deep engagement with national identity, folklore, and Indigenous traditions. Early childhood illnesses, including polio, left her physically vulnerable, and a severe bus accident at age 18 caused lifelong pain and medical complications. This trauma was pivotal in redirecting her ambitions from medicine to art, with her convalescence serving as both a literal and symbolic period of introspection and self-examination.

Frida Kahlo by Guillermo Kahlo, 1932. Sotheby’s.

Kahlo’s early artistic training included lessons from printmaker Fernando Fernández, which exposed her to European techniques and precision. Her early work reflected Renaissance influences and avant-garde movements like Cubism and Neue Sachlichkeit. However, after moving to Cuernavaca with Diego Rivera in 1929, her style evolved to integrate Mexican folk art, pre-Columbian motifs, and religious iconography. She adopted a flattened perspective and vivid color palette, informed by both popular and high art traditions, and drew on Adolfo Best Maugard’s theories of Mexican artistic forms. Kahlo’s work consistently interrogated themes of identity, gender, race, and postcolonial Mexican society.

Portrait of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, 1932. Image by Carl Van Vechten.

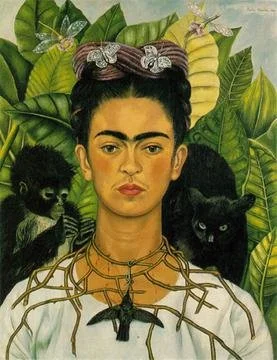

Kahlo is renowned for her introspective self-portraits, which combined autobiographical and symbolic elements. She used her body as a canvas to depict physical and emotional suffering, reflecting both personal pain and universal human vulnerability. Works like Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1940) exemplify her fusion of realism with fantastical, often surreal imagery. Pain, miscarriage, and disability were recurring motifs, articulated with stark clarity and often juxtaposed with symbols drawn from Mexican mythology and Catholic iconography.

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird, 1940. Wikimedia Commons.

Kahlo’s marriage to Diego Rivera brought her into the orbit of prominent artistic and political networks. Her time in the United States (1930–1933) expanded her exposure to American modernism, though she was critical of its capitalist culture. Her narrative style matured in Detroit, where she experimented with retablos, miniature religious paintings, to address themes of suffering, maternity, and national identity. By the late 1930s, she achieved international recognition: André Breton promoted her work as Surrealist, leading to solo exhibitions in New York (1938) and Paris (1939). Though she rejected the Surrealist label, these exhibitions positioned her as an international artist, while reinforcing her identity as a uniquely Mexican voice in the global art scene.

Returning to Mexico, Kahlo increasingly engaged in cultural advocacy. She was a founding member of the Seminario de Cultura Mexicana and taught at the Escuela Nacional de Pintura, Escultura y Grabado "La Esmeralda." Her pedagogy emphasized non-hierarchical, experiential learning and encouraged students to draw from Mexican folk traditions and urban life. Her later work remained intensely personal but continued to intersect with nationalistic and cultural narratives, reflecting the inseparability of her identity from her art.

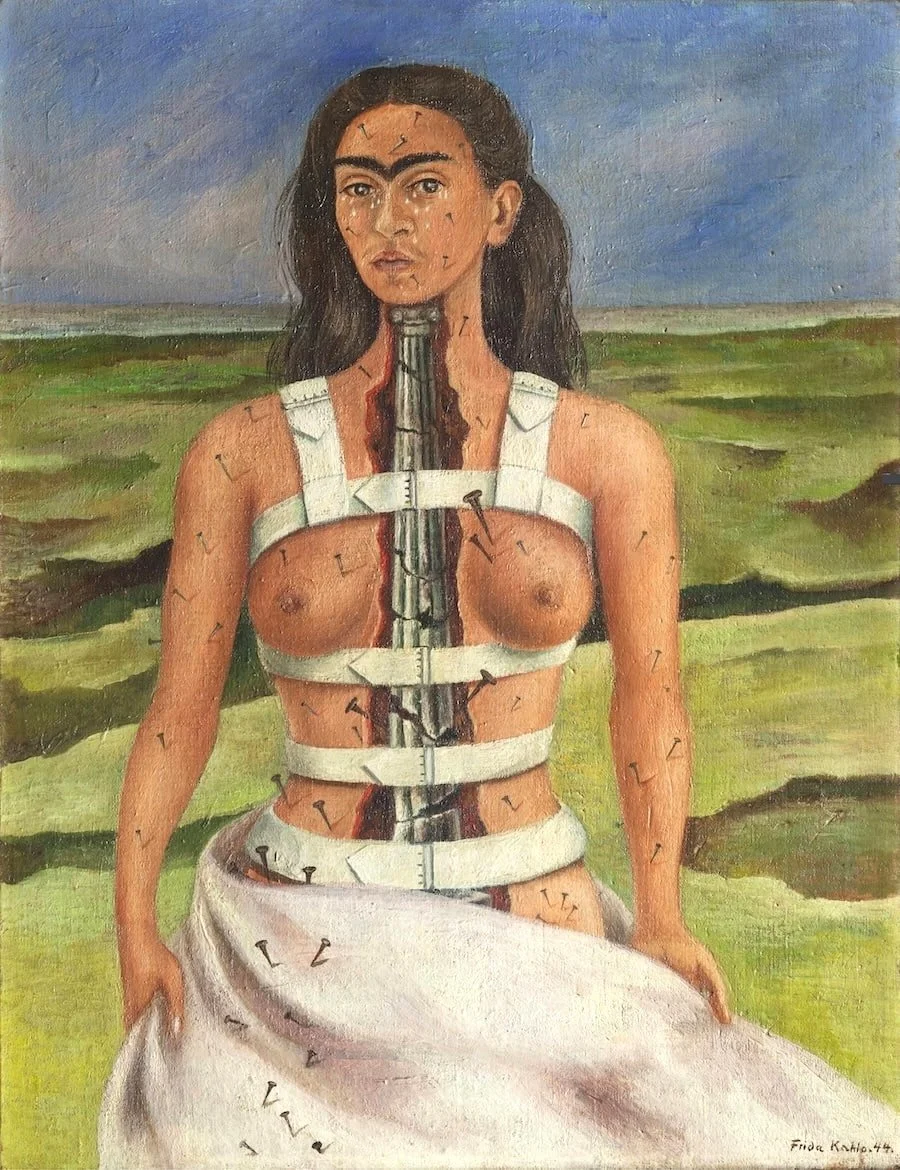

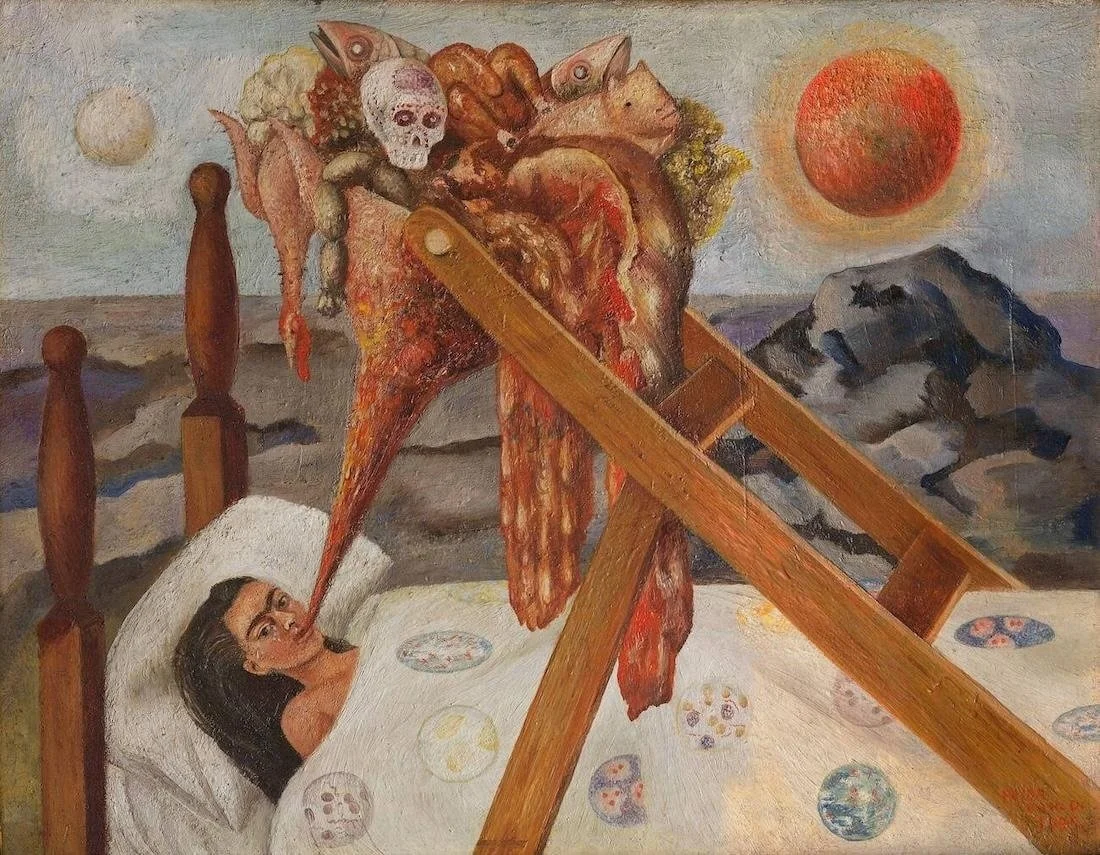

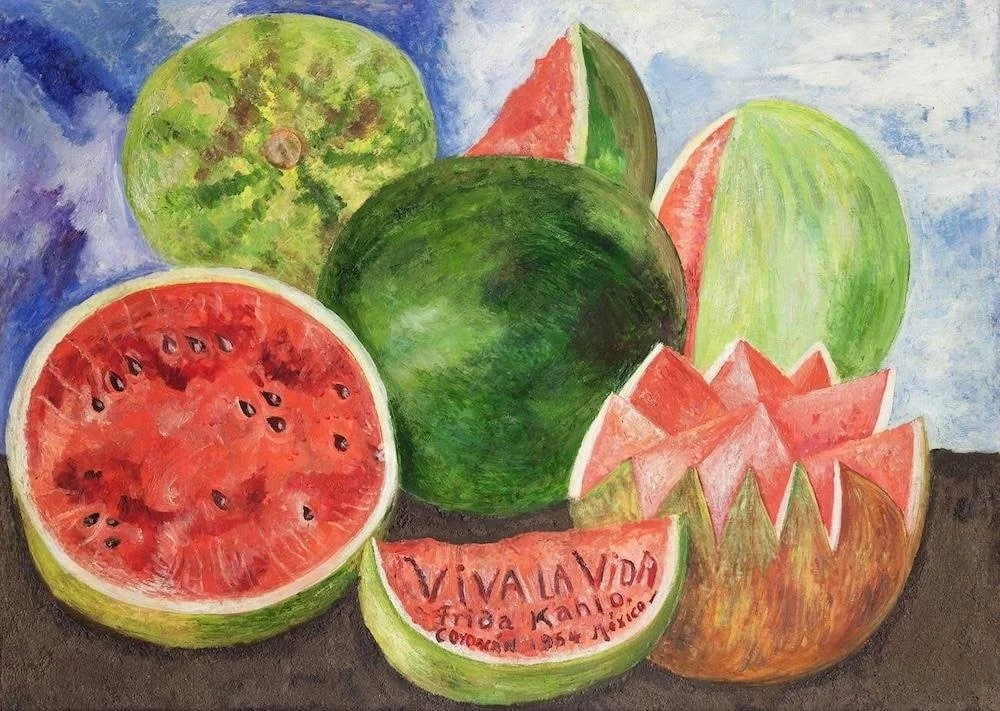

During her later years, Frida Kahlo’s health declined sharply, with spinal surgery failing to improve her condition. Her work from this period including The Broken Column (1944), Without Hope (1945), Tree of Hope, and Stand Fast (1946) reflect her physical suffering. Confined largely to the Casa Azul, she increasingly painted still lifes of fruit and flowers, often incorporating political symbols such as flags or doves. Kahlo expressed a desire for her art to serve the revolutionary communist movement, though her physical limitations constrained her output.

Her style shifted markedly: brushstrokes became hastier, color usage more vivid, and compositions more intense, reflecting both her declining health and heightened emotional urgency. In 1953, recognizing her limited time, photographer Lola Alvarez Bravo arranged Kahlo’s first solo exhibition in Mexico at the Galería Arte Contemporaneo. Defying medical advice, she attended the opening on a stretcher, turning her presence into a symbolic act of resilience. That same year, her work gained international visibility, with five paintings included in the Tate Gallery’s exhibition on Mexican art in London.

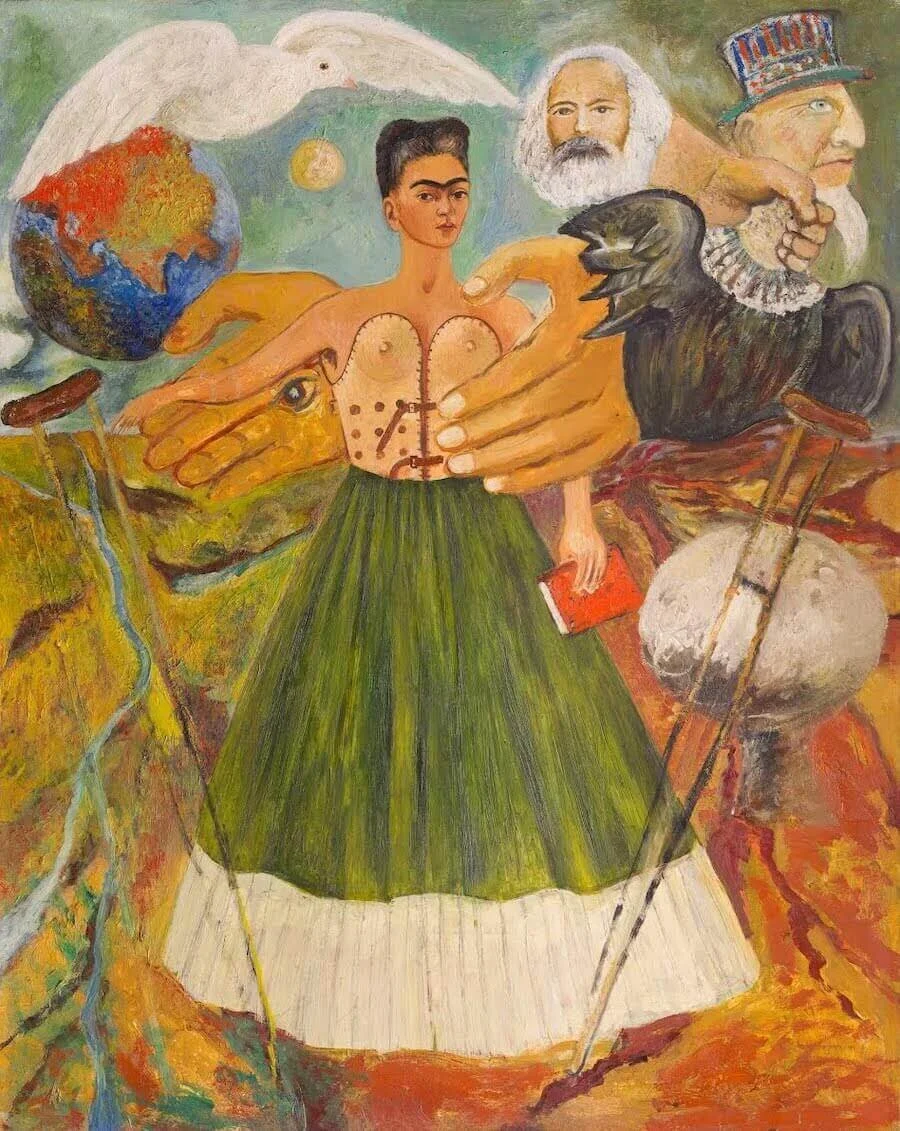

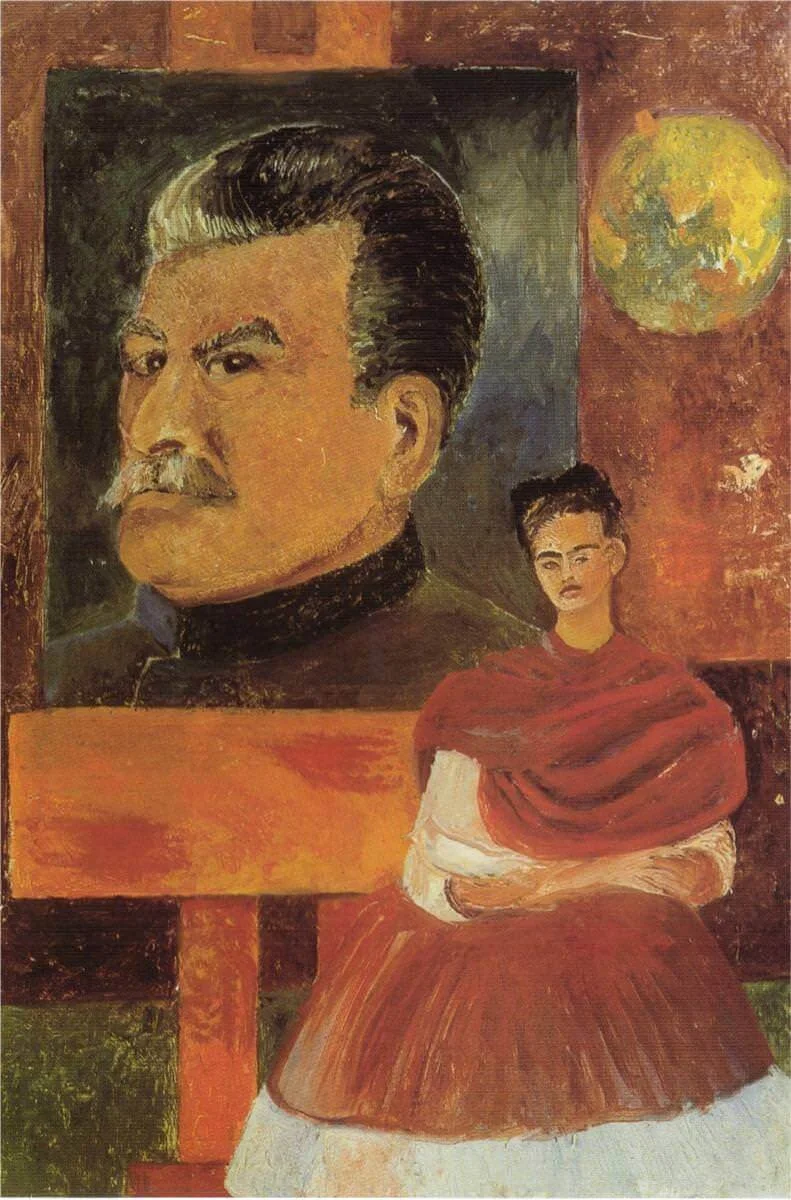

In 1954, after a period of hospitalization and a year-long pause from painting, Kahlo produced her final works, including Marxism Will Give Health to the Sick (c. 1954), Frida and Stalin (c. 1954), and the still life Viva La Vida (1954), maintaining both her political engagement and artistic vitality until the end of her life.

Interpretation and Analysis

In The Wounded Deer, Kahlo externalizes her lifelong splanchnic pain, presenting it as both physical suffering and emotional torment rooted in her fraught relationship with Rivera. Unlike the monumental murals of contemporaries such as Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco, Kahlo’s paintings are intimate in scale. Some scholars interpret this choice as signaling isolation while simultaneously softening the depiction of her pain.

Symbolism plays a central role in communicating her condition and identity. The broken branch, referencing Mexican funerary tradition, acknowledges her deteriorating health, yet the deer's expression conveys resilience rather than anguish. Kahlo’s hybrid depiction, combining human and animal elements and featuring male and female characteristics, reflects both her engagement with pre-Columbian belief systems and her personal exploration of gender and sexuality. In Aztec cosmology, the right foot is associated with the deer, and Kahlo’s birth on day nine, linked to earthly and underworld elements, is echoed in the painting’s compositional motifs: nine trees, nine arrows, and the points of the antlers. The deer's lifted right leg may correspond to Kahlo’s own mobility impairments, representing her physical vulnerability.

Kahlo’s inclusion of male features has been interpreted as an acknowledgment of her bisexuality, while others contextualize it within pre-Columbian hermaphroditic symbolism connecting animals to human anatomy. The word “carma” inscribed on the canvas underscores her belief in fate and reincarnation, framing her misfortunes as the result of past deeds beyond her control. Additionally, Christian imagery, most notably the reference to Saint Sebastian, situates her suffering within a broader spiritual and martyrdom discourse.

The interplay of pre-Columbian, Christian, and Buddhist symbolism in the painting illustrates Kahlo’s multicultural reality and her negotiation of identity across gender, corporeality, and culture. Through these juxtapositions, she presents the self as dynamic and multifaceted rather than fixed, using her own body as both canvas and subject to interrogate the complexities of pain, mortality, and identity.

Conclusion

The Wounded Deer is at once an anatomical record and a moral statement. Kahlo renders suffering with clinical clarity and with a refusal to aestheticise pain into sentimental spectacle. The arrows and the severed limb register injury as persistent fact, while the composed stare of the artist insistently demands recognition rather than pity. The painting therefore operates on two registers at once. On the one hand it documents physical debilitation with an unflinching specificity. On the other hand it stages that debilitation as a site of symbolic negotiation where questions of gender, cultural belonging, and destiny are contested.

Seen in this way, the work becomes an act of testimony. It insists that the viewer attend to the body as archive and to the image as argument. Kahlo does not offer consolation or resolution. Instead she compels the spectator to confront the simultaneous fragility and tenacity of a life lived under recurrent harm. The Wounded Deer endures as a visual statement about what it means to persist when every movement is costly, and about how an individual chronicle of suffering can be transformed into a language capable of speaking to collective histories and to future audiences.