Behind the Painting: Christina’s World by Andrew Wyeth

Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World (1948) stands as one of the most recognisable and enigmatic works in twentieth-century American art. Now housed in the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the painting has become an emblem of American realism, yet its subdued palette, psychological tension, and ambiguous narrative have also invited modernist interpretations. The work’s apparent simplicity of a woman lying in a field gazing toward a distant farmhouse, belies its profound emotional complexity. Through a restrained visual language, Wyeth creates a composition that oscillates between documentary precision and inner expression, rendering the painting both a portrait and a psychological landscape.

The Painting

The composition is dominated by a vast, open field of muted ochres and greens, stretching upward toward a cluster of weathered buildings at the horizon. The low vantage point draws the viewer’s gaze across the uneven terrain, following the woman’s line of sight toward the farmhouse. The central figure, Christina, lies in the foreground with her torso twisted and arms extended behind her, suggesting both motion and limitation. Her pale pink dress contrasts subtly with the sun-bleached grass, while the earth tones unify the figure and landscape in a shared quietude.

Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World , 1948.

Wyeth’s tempera technique (resembling trattegio) heightens the tactile qualities of the scene. Each brushstroke contributes to a sense of brittle texture—the roughness of dry grass, the coarseness of fabric, the parched soil beneath. The precision of detail does not merely serve realism but evokes an awareness of the material world that borders on metaphysical. The absence of overt narrative markers scuh as the woman’s expression, the reason for her position, the emptiness of the space, invites a deeper reading of psychological and emotional resonance.

The Artist

Andrew Wyeth (1917–2009) was a central yet contested figure in twentieth-century American art. Working primarily in tempera and watercolor, he pursued an approach often described as “magic realism”—a term denoting his fusion of representational accuracy with emotional and symbolic undercurrents. Wyeth’s art resists the formal abstraction dominating postwar modernism; instead, he focused on intimate depictions of rural life in Pennsylvania and coastal Maine. His preference for subdued tones, meticulous craftsmanship, and solitary subjects situates his work within an American realist tradition descending from Thomas Eakins, yet his psychological intensity aligns him more closely with the Symbolists.

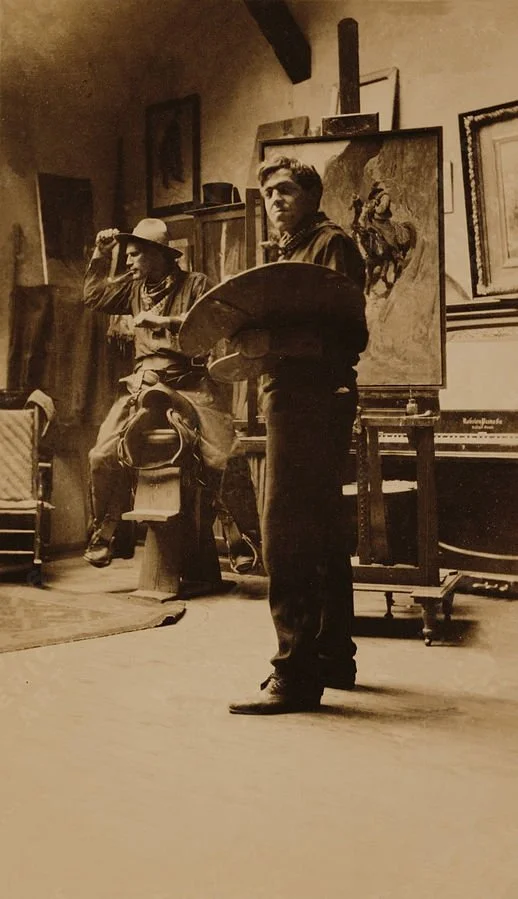

N. C. Wyeth in his studio in Delaware, at work on his painting, Rounding-up, Little Rattlesnake Creek, 1904,. The model is possibly Allen Tupper True. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

Wyeth’s relationship to modernism was ambivalent. Critics in the mid-twentieth century often dismissed his realism as nostalgic or conservative, yet his attention to the internal life of his subjects suggests a parallel engagement with existential modernity. His paintings frequently blur the boundary between observation and projection, between landscape and psyche, revealing his persistent concern with isolation, mortality, and the quiet drama of everyday existence.

Inspiration Behind Christina’s World

The painting was inspired by Wyeth’s neighbour, Anna Christina Olson, who lived in a farmhouse near the artist’s summer home in Cushing, Maine. Olson suffered from a degenerative muscular disorder (likely Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease) that severely limited her mobility. Refusing to use a wheelchair, she instead moved across the ground by dragging herself with her arms. Wyeth observed her one day from a window, and this image became the genesis of Christina’s World.

While the composition is based on a real person and setting, the Olson House still stands as a historic site, the final work departs significantly from direct realism. The figure’s body, for example, was modelled on Wyeth’s wife, Betsy, rather than Christina herself, creating a composite image that intertwines observation and imagination. Wyeth thus transforms a scene of physical limitation into a meditation on endurance and inner life.

The Olson House as depicted in its current condition as of August, 2018. Image taken by Ryan Prescot available on Wikimedia Commons.

Thematic Analysis and Interpretation

At its core, Christina’s World explores themes of isolation, resilience, and perception. The vastness of the field, juxtaposed with the diminutive figure, produces a sense of existential distance. Christina’s gesture, reaching yet grounded, embodies both longing and acceptance. Her gaze toward the farmhouse may suggest a yearning for home, stability, or self-sufficiency, yet her physical position underscores the inaccessibility of those ideals.

Wyeth’s restrained palette amplifies this emotional ambiguity. The subdued tones and desaturated light evoke both serenity and melancholy. Critics have read the painting alternately as a symbol of American perseverance, an image of the rural spirit in adversity, and as a psychological self-portrait reflecting Wyeth’s own sense of confinement and detachment.

The absence of human activity within the farmhouse or landscape reinforces a haunting stillness, leaving the viewer suspended between empathy and voyeurism. Wyeth’s precision of detail does not provide clarity but rather deepens the sense of mystery. The realism of the surface conceals an emotional abstraction beneath, wherein physical landscape becomes a metaphor for interior experience.

Broader Cultural Context

Created in 1948, Christina’s World emerged in the aftermath of World War II, at a time when American art was dominated by Abstract Expressionism. In contrast to the gestural intensity of Pollock or de Kooning, Wyeth’s subdued realism appeared anachronistic. Yet, his work resonated deeply with a public searching for familiarity and emotional authenticity. MoMA’s acquisition of the painting, championed by curator Alfred H. Barr Jr., signalled an institutional recognition of realism’s continued relevance within modern art discourse.

The painting also engages with a distinctly American sense of place. Its weathered architecture and barren landscape evoke both nostalgia and endurance, reflecting the complexities of rural identity in postwar America. Wyeth’s vision of the ordinary is not sentimental but imbued with the uncanny, a quiet revelation of the human condition embedded within the everyday.

Conclusion

Christina’s World endures because it resists closure. It is at once specific and universal, intimate and remote. Through disciplined realism and psychological depth, Wyeth captures the tension between physical limitation and inner vastness—a tension that mirrors the human struggle for meaning within constraint. The painting’s enduring power lies not in what it reveals, but in what it withholds: a space for projection, empathy, and reflection that continues to engage viewers across generations.