Shakespeare Recovered: Durham’s First Folio on Display

For the first time in over a decade, Durham University is placing one of the world’s most significant literary treasures at the centre of a major exhibition. Shakespeare Recovered focuses on Durham’s copy of the First Folio, the landmark 1623 publication that preserved half of Shakespeare’s plays for posterity. This volume does not simply sit in a case as a rare book. Instead, it is presented as the focal point of an exhibition that draws attention to the complex story of loss, rediscovery, and the modern science of conservation.

Durham’s First Folio once resided within Bishop Cosin’s Library, where it had been held since the seventeenth century. In 1998, the book was stolen and disappeared for a decade. It resurfaced in Washington D.C. in 2008, when it was taken to the Folger Shakespeare Library. Analysis confirmed it was Durham’s missing copy, but its condition had been severely compromised: the cover was gone, pages were missing, and the spine had been destabilised.

The Folio was returned to Durham in 2010. From that point onwards, it became the subject of extensive conservation analysis and debate. The exhibition traces this process in detail, showing how the Folio’s story extends beyond Shakespeare’s plays to encompass the realities of cultural stewardship. Visitors are guided through the stages of recovery and preservation, making conservation not a hidden task carried out behind closed doors, but the main interpretive thread of the exhibition.

A major feature of Shakespeare Recovered is its use of technology to uncover the Folio’s hidden history. Spectroscopy enables precise examination of colour, while infrared imaging brings to light annotations and doodles that have lain invisible for centuries. These discoveries emphasise that the Folio is not only a textual monument but also a material object with a life shaped by readers, owners, and even vandals.

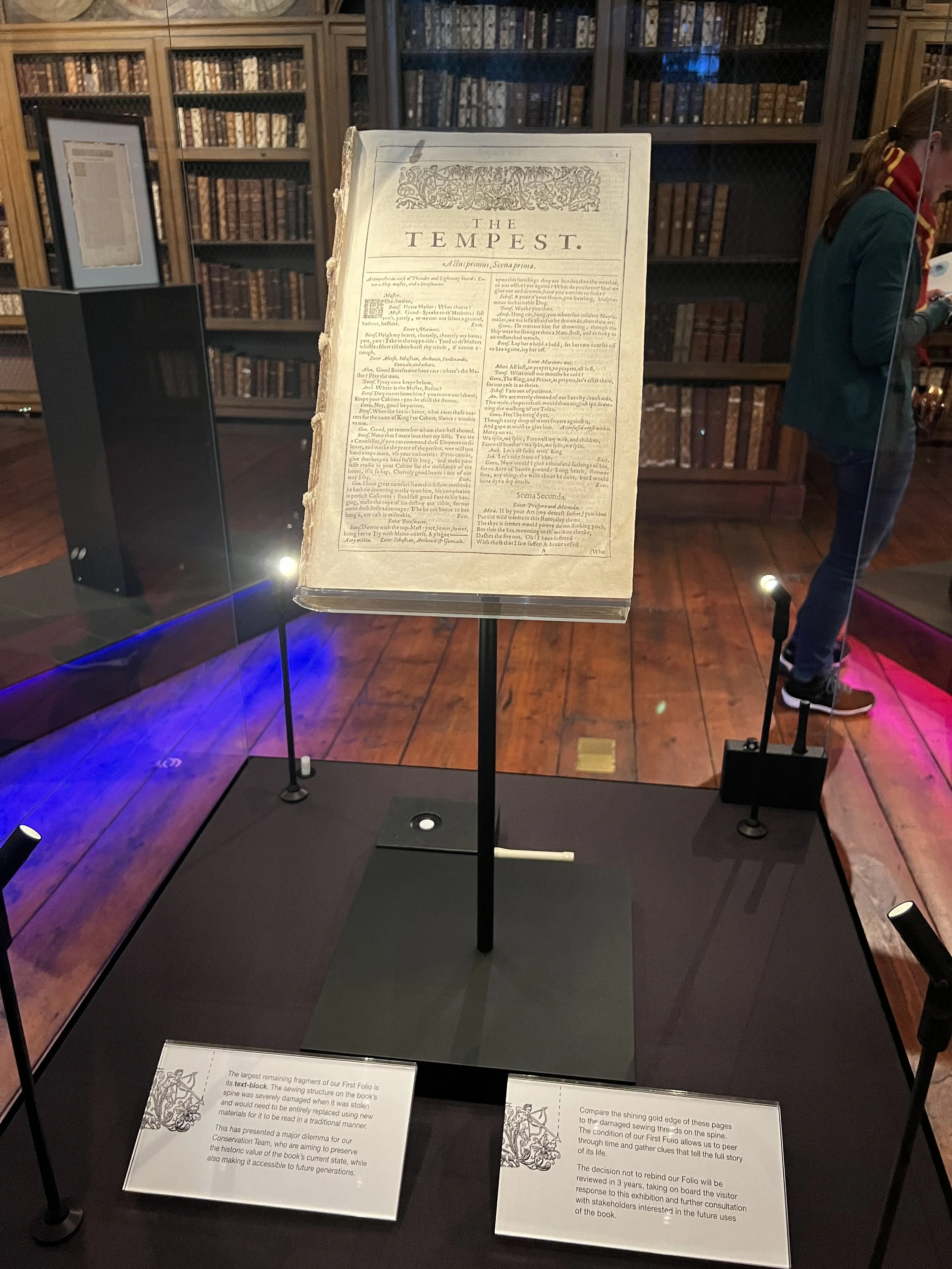

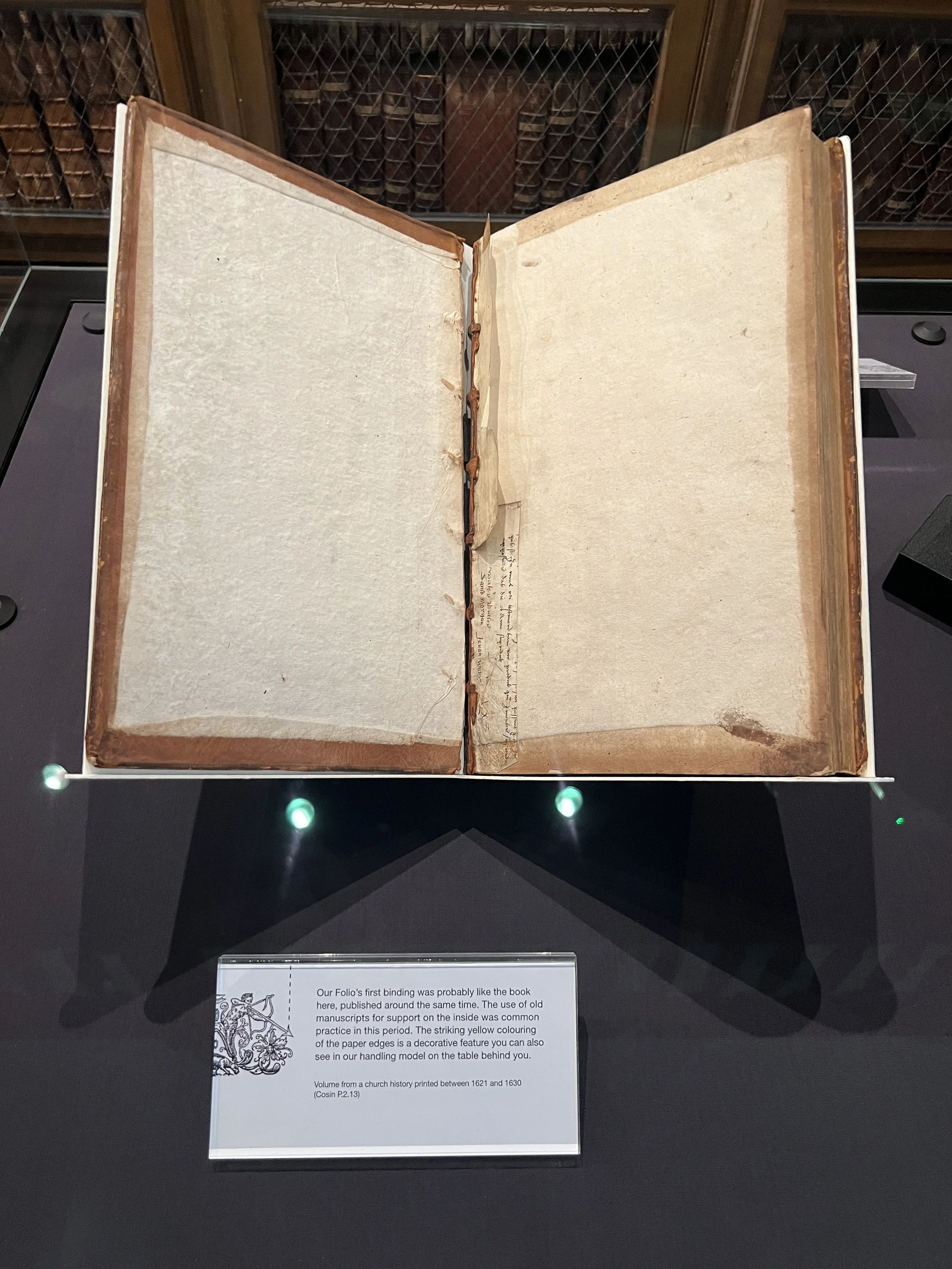

The Folio’s damaged condition paradoxically allows scholars to see aspects of early bookmaking that are usually concealed. The removal of the cover has left the spine exposed, revealing evidence of its seventeenth-century binding. For visitors, this provides an opportunity to observe the methods of book production in Shakespeare’s time, insights that more intact copies cannot easily provide.

The emphasis of the exhibition lies not simply on displaying a rare book but on foregrounding the dilemmas of conservation. Visitors encounter an interactive element that allows them to take on the role of conservators, weighing the possible futures of the Folio. Should it be rebound with a protective new cover, or should its current damaged condition be left visible as part of its history? Each option carries interpretive consequences. A new cover would safeguard the book but obscure the evidence of its theft and recovery. Leaving it exposed would allow continued study of its structure but might limit its durability.

By staging this dilemma, the exhibition turns conservation into an active and public process. The Folio becomes a site of decision-making where ethical, historical, and practical considerations converge. This emphasis on conservation practice distinguishes Shakespeare Recovered from exhibitions that simply present rare books as static relics. Instead, Durham’s exhibition invites the public to engage critically with the ongoing care of cultural heritage.

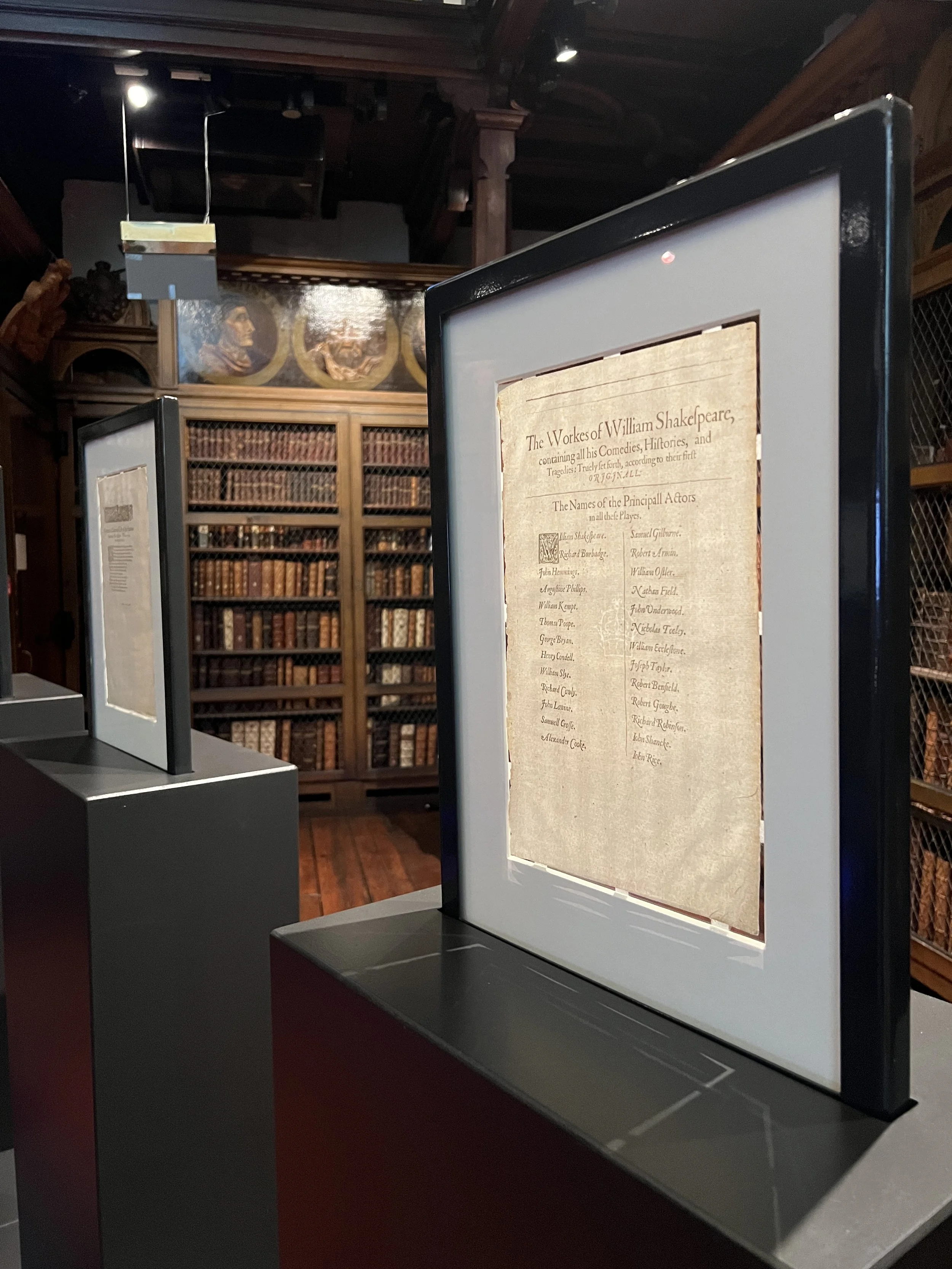

While the narrative of theft and recovery is compelling, the exhibition continually situates Durham’s copy within the larger context of the First Folio’s significance. Published in 1623, the First Folio was the first collected edition of Shakespeare’s plays, printed only seven years after his death. It contained 36 plays, 18 of which, including Macbeth and The Tempest, had never appeared in print before. Without this publication, many of Shakespeare’s most famous works might have vanished from history.

Durham’s copy was acquired by Bishop John Cosin in the 1620s and later placed in his library in 1669. Out of approximately 750 original copies, only about 235 survive today. Each surviving copy is unique, with distinctive features that reveal aspects of printing practices and ownership. This individuality also allowed scholars to confirm beyond doubt that the damaged copy recovered in Washington was indeed Durham’s missing Folio.

What sets Durham’s Folio apart is its extraordinary narrative of damage and survival. The exhibition makes clear that the book’s scars are not merely signs of loss but also sources of knowledge. As Stuart Hunt, Director of University Library and Collections, observes:

“Shakespeare’s First Folio is a literary wonder of the world, but only Durham’s First Folio can tell such a unique and powerful story. The vandalism it sustained left the Folio extremely vulnerable. But with this comes an opportunity to closely examine an iconic object in new ways and discover more about Shakespeare’s world and legacy.”

The exhibition underscores this paradox. The Folio is vulnerable, but its vulnerability creates conditions for fresh study and new discoveries. It testifies to the risks cultural artefacts face, yet also to the capacity of conservation to uncover, interpret, and protect.

Shakespeare Recovered is not simply an exhibition of a rare book. It is an exploration of how an iconic object can be damaged, rediscovered, and conserved, and how those processes themselves can generate new knowledge. The Durham First Folio demonstrates the enduring importance of Shakespeare’s plays, but it also illustrates the fragility of cultural heritage and the intellectual value of conservation practice. By foregrounding the work of recovery and preservation, the exhibition positions Durham’s Folio not only as a literary treasure but also as a case study in how history is continually reshaped through the objects that survive.