At What Point Does Art Become Controversial?

Art has always had the capacity to provoke — whether admiration, confusion, offence, or debate. But when does a work of art become controversial? The answer does not lie in whether a single person finds a piece distasteful or inappropriate. Rather, controversy arises when a work creates significant disagreement within the art world, the general public, or both. It is not necessarily about moral outrage, but about public discourse: contested meaning, blurred boundaries, or unresolved discomfort.

Crucially, controversy is not static. What one generation considers transgressive might become foundational for the next. Consider the Salon des Refusés of 1863, which displayed works rejected by the Paris Salon, including those of Édouard Manet, and scandalised critics and audiences. Today, these same artists are central to the narrative of modernism. Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine du Monde (1866) was long hidden from public view due to its explicit nature but is now recognised as a bold expression of realism and a milestone in the representation of the body. In such cases, once-subversive works are absorbed into the canon, their controversial status reframed as part of their historical importance.

Gustave Courbet, L’Origine du Monde, 1866. oil on canvas. 46 × 55 cm. Musée d’Orsay.

The reverse can also happen. Some works that were widely accepted at the time of their creation now provoke unease or criticism. Paintings by Paul Gauguin, for instance, once admired for their formal qualities, are now scrutinised through postcolonial and ethical lenses due to their exploitative contexts and subjects.

Paul Gauguin, Parau Api. What's new?, 1892. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Balthus’s portrayals of adolescent girls, long exhibited without question, are today subject to growing discomfort among viewers and curators alike. In both examples, shifting values have reactivated the potential for controversy.

Balthus, Thérèse Dreaming, 1938. Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London

A recurring factor in these shifts is the way artworks challenge either the definition of art or the morality of their time. Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), a urinal presented as sculpture, posed a direct challenge to institutional and aesthetic conventions. It did not shock through content but through context, by asking whether authorship and designation alone could transform an object into art.

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917. Photographed by Alfred Stieglitz at 291 art gallery following the 1917 Society of Independent Artists exhibit, with entry tag visible. The backdrop is The Warriors by Marsden Hartley.

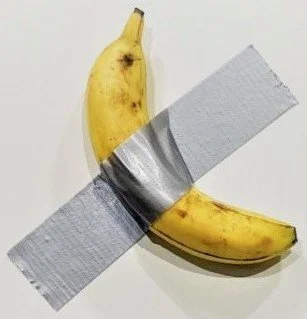

Nearly a century later, Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian (a banana duct-taped to a wall) echoed this provocation. The question these works ask is not “Is this good?” but “Is this art?”

Maurizio Cattelan, Comedian, 2019.

Other controversies are grounded in the moral and social realm, works that provoke because they subvert public values or depict difficult, often traumatic, subject matter. Marcus Harvey’s Myra (1995), a portrait of the child murderer Myra Hindley made from children’s handprints, sparked widespread protest. It was not merely the subject that disturbed viewers, but the method of execution, the choice of materials, and the perceived insensitivity to victims. The outrage was not limited to aesthetic dislike but extended into questions of ethics and responsibility.

Marcus Harvey, Myra, 1995.

But controversy is not always obvious or universal. A useful strategy for assessing where a work becomes controversial is to trace a gradient of public agreement. Begin with artistic practices widely accepted across cultures and institutions, and then move step-by-step toward more contested terrain. Somewhere along that path, you’ll reach a point where opinions sharply divide, where there is no majority consensus about whether something is legitimate, valuable, or even tolerable. That is often the threshold of controversy.

This exercise reveals an essential truth: controversy is not fixed in the work itself, but in the relationships between work, viewer, and context. Even the artist’s intent, while relevant, cannot resolve a controversy, because the meaning of art is negotiated in its reception. For instance, a work exploring body image through sexually explicit self-portraiture may be read as empowering by some and inappropriate or exploitative by others. If the subject depicted is a minor, even if portrayed symbolically, or as a fictional figure, reactions will likely diverge more sharply. In such cases, questions of agency, harm, consent, and representation collide.

These grey zones matter. Somewhere in the space between provocation and harm, between expression and exploitation, lies the terrain in which controversy operates. Art that remains within clearly defined boundaries may be easier to categorise, but rarely generates the same intensity of public reflection. Controversy is often where art begins to matter, to disrupt assumptions, to demand critical engagement, to test the limits of what we accept and why.

Understanding controversy in art, then, is less about policing boundaries and more about noticing where they blur. These are the moments where discussions intensify, where values clash, and where the definition of art itself is up for debate. Rather than trying to fix these boundaries permanently, we might better ask what the controversy reveals, about the artwork, the artist, and most of all, about ourselves.