Understanding Condition Reports: Why Do They Matter?

In the field of painting conservation, condition reporting forms the foundation of responsible intervention. Before any treatment begins, a detailed assessment is required to document the current physical state of a work of art. This process, often undertaken by conservators or trained professionals, results in a written condition report, a structured account that plays a vital role in both short-term decision-making and long-term preservation.

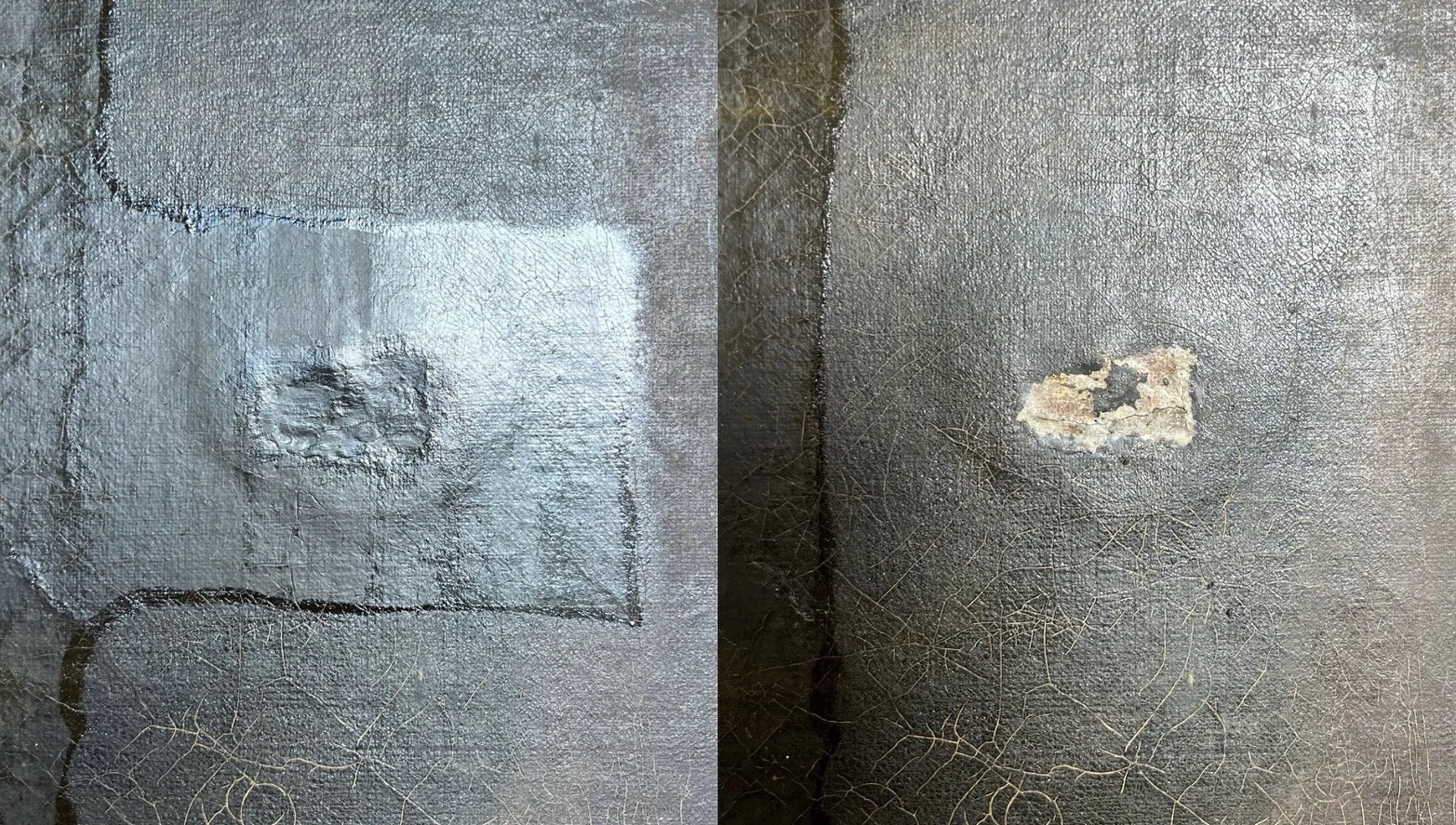

I’ve recently added a dedicated section on my website where you can view examples of condition reports I’ve produced. These reports demonstrate not only the technical language used in conservation but also how visual and written documentation come together to form a useful historical and practical resource.

Why Condition Reports Are Useful

Condition reports serve multiple purposes. Primarily, they offer a formalised record of a painting’s material condition at a specific moment in time. This includes observations about deterioration, previous restoration attempts, and structural or surface issues. As such, they are essential for planning any conservation treatment.

They also serve as baseline documentation that can be referenced over time to monitor changes, assess the impact of environmental conditions, or inform insurance claims and loan agreements. Even in cases where treatment is not anticipated, condition reports may be commissioned to support grant applications, acquisitions, or risk assessments in storage and display contexts.

When Are Condition Reports Used?

Condition reports are commonly produced at several key moments in an artwork's life cycle:

Before treatment: To identify areas of deterioration, prioritise risks, and inform treatment proposals.

After treatment: To provide documentation of any alterations or stabilisation work carried out.

Prior to loan or transport: To record condition for liability, risk mitigation, and insurance purposes.

During acquisitions or sales: As part of due diligence processes, especially for high-value works.

In collection surveys: To monitor groups of paintings over time and support preventative conservation strategies.

These reports are indispensable not only during active conservation work but also in preventive contexts. Even when no immediate treatment is planned, condition reporting can help to anticipate future vulnerabilities, justify funding applications, or simply act as a baseline for future comparison.

What Does a Condition Report Include?

Condition reports typically follow a standard structure, documenting a painting layer-by-layer, from the support to the surface. A thorough report may include the following sections:

Object information: Title, artist (if known), dimensions, medium, date, accession or inventory number, and photographic documentation (front, reverse, and details).

Auxiliary support condition: Stretcher, strainer, or backing board—assessment of structural integrity, tension, and evidence of past intervention.

Primary support condition: Canvas, panel, copper, or other substrate—assessment of deformations, tears, splits, or woodworm.

Ground layer: Description of colour, thickness, adhesion, and any signs of cracking, flaking, or delamination.

Paint and media layers: Examination of paint stability, cracking patterns, abrasion, pigment loss, or evidence of retouching.

Varnish and surface coatings: Characterisation of gloss, discolouration, unevenness, and surface accretions.

Frame and glazing (if applicable): Assessment of structural condition and impact on the object.

Previous interventions: Visual or UV evidence of overpaint, fills, cleaning residues, or lining.

Specialist tools such as UV light, infrared reflectography (IRR), raking light, and magnification may be used to identify details not visible under ambient lighting conditions. Photographic documentation is typically embedded within or appended to the report, often annotated to highlight damage or alterations.

Complementary Forms of Documentation

While the condition report forms the central written record of an object’s current state, it is typically accompanied by other documentation that builds a more complete understanding of the artwork:

Treatment proposals and reports outline the rationale, objectives, and methods of conservation interventions.

Technical examination reports (e.g. pigment analysis, cross-section microscopy, XRF, FTIR) provide material characterisation to support treatment decisions.

Photographic records include high-resolution, UV, IR, and raking light images before, during, and after treatment.

Environmental records (e.g. RH, temperature, light levels) may support observations of damage related to display or storage.

Together, these documents form a cohesive and transparent record of conservation activity, supporting future decision-making by other professionals or caretakers.

Why Condition Reports Matter to Owners, Institutions, and Researchers

Condition reports are not only useful to conservators, they are also valuable to collectors, institutions, insurers, researchers, and legal professionals. For private owners, such reports can offer peace of mind when loaning or transporting artworks, and they are often required for insurance valuations or claims. For institutions, they provide a vital internal record, especially in cases of shared ownership, large collections, or frequent exhibition rotation.

From a research perspective, condition reports provide insight into the material history of a painting, including signs of alteration, historic conservation practices, or workshop techniques. They help reconstruct an object’s biography (what has changed, when, and why) and preserve this history for future interpretation.

In many cases, condition reports also reveal more than what is visible to the naked eye. Damage may be cumulative, slow to develop, or previously concealed. Subtle signs such as blanching, raised cracks, or embedded dirt can indicate more complex deterioration. The trained eye of a conservator, supported by the appropriate tools, ensures that nothing critical is overlooked.

Conclusion

To support better public engagement with these processes, I have now added a dedicated section to my website showcasing anonymised examples of condition reports and related conservation documentation. This aims to demystify what such documents look like and how they are used in real-world conservation settings. These examples reflect best practices in easel painting conservation and are formatted according to current academic and professional standards. They may be useful for students, collectors, or institutions seeking clarity on what to expect from a condition report.

Condition reports should not be seen as static documents, but as active tools in the stewardship of cultural heritage. They inform conservation ethics, shape treatment options, and record the material biography of paintings across time. Whether produced in response to an immediate conservation need or to establish a baseline for monitoring, their value lies in their precision, clarity, and accessibility. Making this form of documentation more visible and better understood is a key step toward more informed conservation conversations—something I hope to support through both my practice and this new resource.